How the pullback followed Messi’s Barca and changed the Prem

You can’t tell the story of the 2023-24 Premier League season without a certain eight-letter world: the pullback.

The first goal of the season, and the one that restarted Manchester City‘s title defense, came from a pullback. And so did the most recent one that might decide the title race, when Kai Havertz on Sunday dribbled toward the end line and then — as the name suggests — pulled the ball back for Leandro Trossard in front of the net, creating Arsenal‘s winning goal over Manchester United.

Goals are way up in the Premier League this season, and uncoincidentally, so is perhaps the single most dangerous pass in the sport: the driven ball from near the end line, against the defense’s momentum, back toward the penalty spot. The pullback — also called a cutback — is driving Arsenal’s title challenge. It’s also why Manchester City kept winning the league, but might not this year.

While the pullback was once the province of only the richest teams in any given league around the world, like Lionel Messi‘s Barcelona, it has been spreading. The maneuver that has long been used to great effect in Spain is now trendier than ever before across the Premier League, where just about every team has developed an obsession with it.

No matter what the table looks like at the end of next weekend, the pullback has become the pass that defines the Premier League.

Lessons from Messi, and why the pullback works

At the highest level of the sport, the pullback was popularized by Barcelona at the beginning of the last decade. The platonic ideal featured a diagonal through-ball from Lionel Messi to an overlapping Jordi Alba, who then played a pullback toward the penalty area for an onrushing Messi to finish off the pass.

Since 2010, there have been seven seasons across Europe’s big five leagues in which a team scored at least eight goals from pullbacks — and four of them came from the dominant Barcelona teams featuring Messi and Alba. Over that same stretch, Alba registered 18 assists from pullbacks, while no other player has created more than 10. And Messi scored 24 goals from pullbacks — nobody else has more than 16.

As this graphic with all of Alba’s LaLiga assists to Messi shows, most of them came from passes inside the box that are then played away from the goal:

And therein lies the key to the pullback’s effectiveness. Defenders, instinctively, are defending the goal — especially when the ball gets so close to the goal. To defend the goal, you drop closer to the goal. But a pullback essentially uses traditional defender instincts to destroy a defense.

Messi is the best at pretty much everything, but a classic 2014 paper showed he was also the best at walking. It’s not that he’s lazy — though it is an energy conservation technique as well — but rather it’s that most soccer players are taught to be in a constant state of movement, which leads them to vacate high-value areas on the field as they chase after an opponent or the ball. While Messi can brilliantly create space for himself with the ball, when he’s out of possession, he’ll let the opposition create the space for him and then just stand there.

This is exactly what happens with a pullback. As the attacking team drives the ball toward the end line, the defenders naturally scramble back toward their goal line, which creates seams inside the most valuable area of the field: the penalty box. A manager with Champions League experience told me his teams train for these specific moments, and he credits Pep Guardiola for popularizing the tactic.

“The finisher is within the penalty area — usually between 12 yards out and goal — the goalkeeper is recovering to the center of the goal or is out of the equation entirely, and the defenders are forced to face their own goal,” said Carlon Carpenter, head of video analysis with the Houston Dynamo. “So even if the pass fails, errors can occur on their end or lead to corners and regains for the attacking team.”

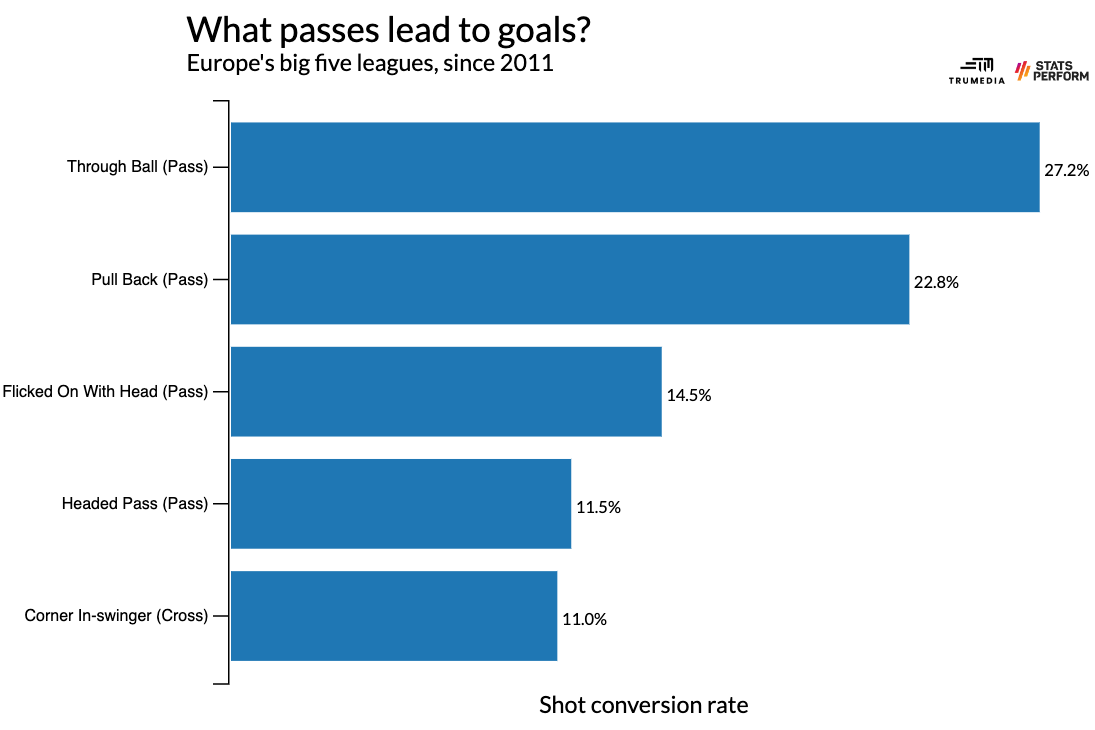

Carpenter is something like the Internet’s preeminent scholar of pullbacks (or “cutbacks,” as he calls them). In 2021, he co-authored a series called “Where Goals Come From” with analyst Jamon Moore for the website American Soccer Analysis. They found (among other things) that shots from pullbacks had the second-highest conversion rate of any pass, behind only through-balls:

— Carl Carpenter (@CarlonCarpenter) May 12, 2024

“Ninety-seven percent of the shots from cutbacks we profiled were in the ‘good to great’ expected-goal tiers,” he said. “That’s anywhere from a 24% to 54% conversion rate from these shots.”

Looking at Stats Perform’s data paints a similar picture. Across the big five leagues since 2011, shots from through-balls have been converted 27.2% of the time, while pullbacks aren’t far behind. Everything else is, though. These are the types of passes with the five highest conversion rates:

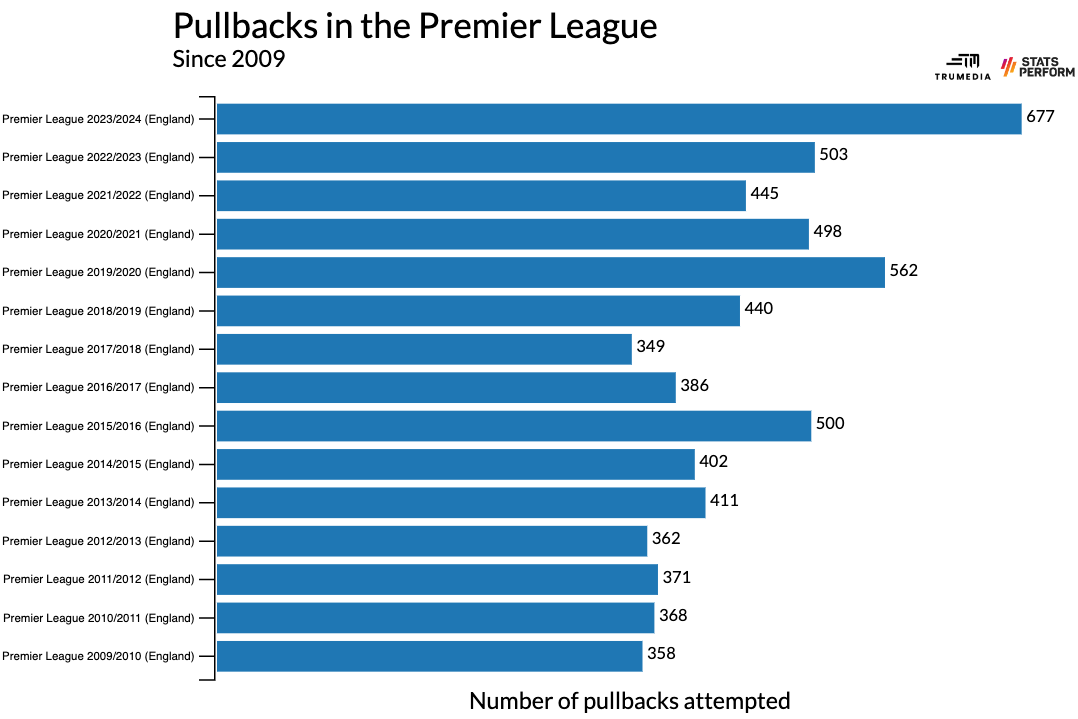

And one reason we’re seeing so many goals in the Premier League this season is that teams are playing more pullbacks than ever before:

That’s more than 100 more than in any previous season, and there’s still a full matchday left to play.

How Arsenal pulled Manchester City back

They might not win the league, but there’s a decent chance Arsenal will still manage to set a record Sunday. Per Stats Perform, the most pullbacks in a season were attempted by Barcelona in 2012-13 with 71. Second most is a tie between 2015-16 Arsenal, a team that Mikel Arteta played for, and this season’s Arsenal, a team that Mikel Arteta manages, with 68. Four more pullbacks and these Gunners will etch their names in (the) history (of a very specific database that most people don’t have access to).

Arsenal, too, serve as an explanation for why we’re seeing so many pullbacks in the Premier League overall. As I wrote about toward the end of last season, the attacking fullback is a dying breed. In an effort to create more solidity both with and without the ball, the likes of Arsenal and Manchester City have both started to play one, if not two, conservative fullbacks who don’t overlap toward the end line but instead either pinch in as a third center back or slide into the midfield.

At the same time, thanks to the influx of playing and coaching talent driven by the league’s increasing financial dominance, Premier League defenses are as organized as ever and quite difficult to break through. (The same isn’t necessarily true of Europe’s other big leagues, which is maybe why there hasn’t been a similar stark rise in pullbacks.)

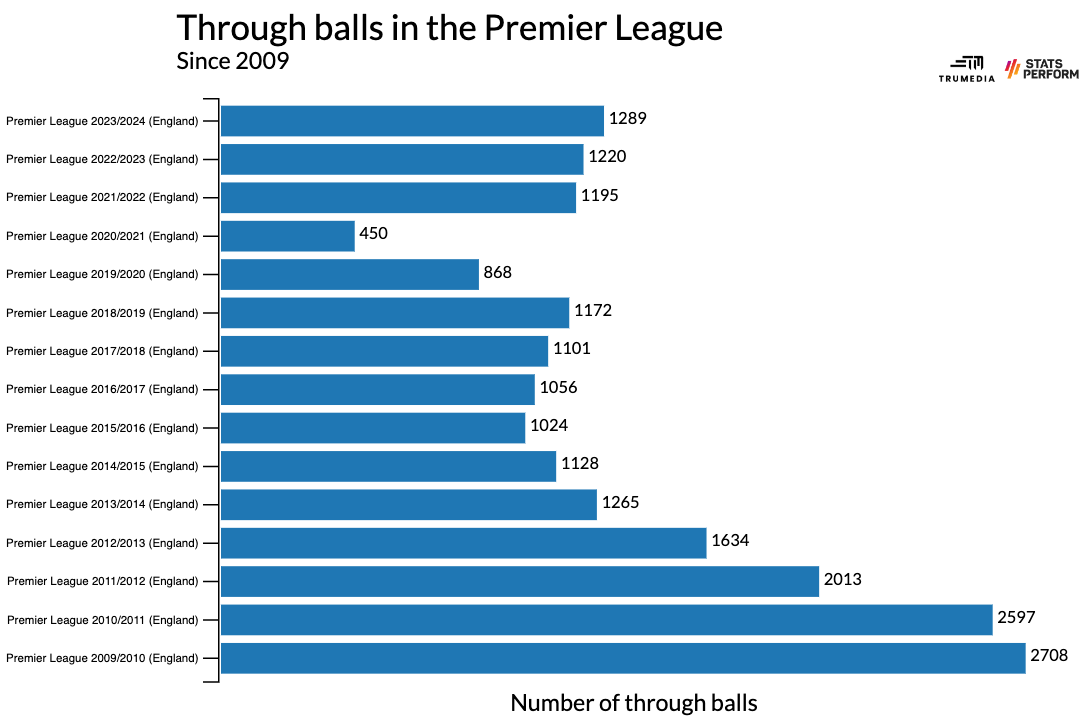

The reason through-balls lead to so many goals is that by definition of the stat, when a player receives a through-ball, he’s behind the opposition defense. So, if he takes a shot, he’s taking a clear shot from a one-on-one with a goalkeeper. However, defenses are increasingly taking away through-ball opportunities. There’s likely some data-collection wonkiness in here — see: the drop-off in 2020-21 — but the broad trend is what matters:

This year’s numbers, in particular, are inflated a decent amount by the extra game time. It’s just way harder to complete a through-ball than it used to be. But if that’s true and teams aren’t pushing their fullbacks forward to get around the outside of the back line or stretch the opposition horizontally, then how the heck do you create quality goal-scoring opportunities? Set pieces are one way, but from open play, the answer is the pullback.

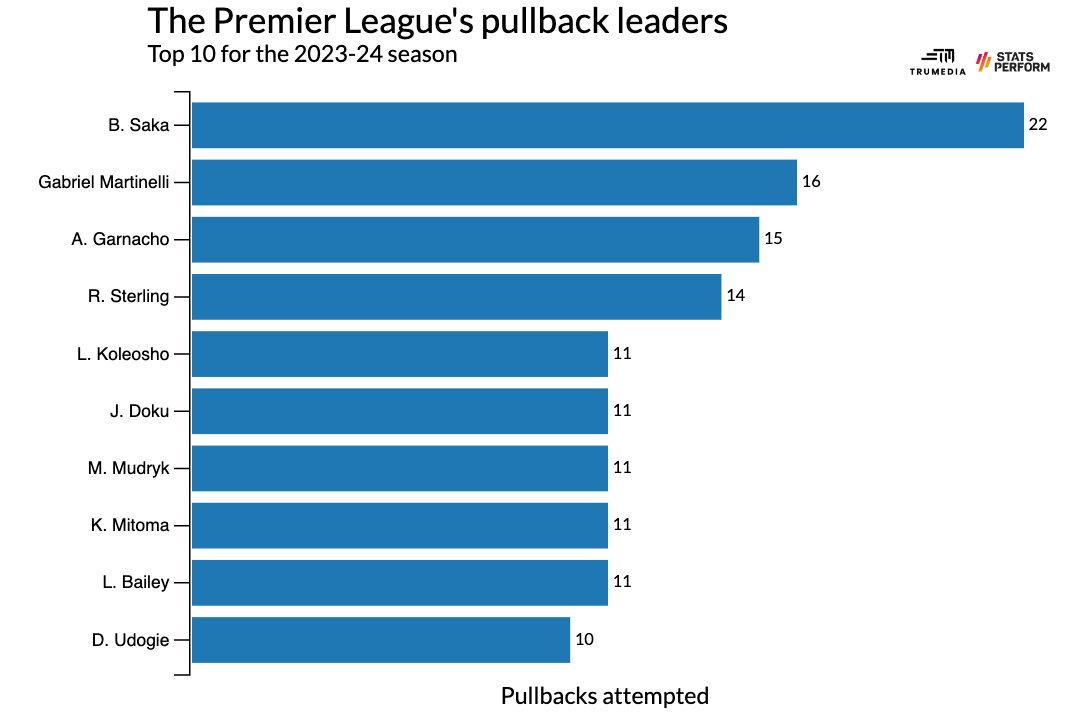

Rather than having a fullback like Alba play the pullback, it’s almost always a traditional winger breaking toward the end line and then cutting the ball back against the defense’s momentum these days. There’s only one fullback, Tottenham’s Destiny Udogie, in the top 10 for pullbacks attempted this season. Unsurprisingly, the list is led by both of Arsenal’s wingers, Bukayo Saka and Gabriel Martinelli:

The rise of the pullback coincides, somewhat, with the near-death of the traditional center-forward role. Given the location of a center-forward on the field, his role in a cutback situation is rarely to finish off the cutback. These players aren’t supposed to be trailing the play. Instead, the center-forward’s role is to draw defenders away from the center of the box so someone else can run into that space and score the goal.

“It requires good movement in the box from center-forwards,” Carpenter said. “The first run of the attacker should be as hard as possible across the goal to force defenders deeper. And then there come runs from the wingers, attacking midfielders, or central midfielders, to attack seams behind the defense. It’s also a game of patience to keep switching the ball and forcing the opposition to shift repeatedly.”

This fits Arsenal’s personnel quite well, as Havertz and Gabriel Jesus are all-around attacking contributors rather than out-and-out goal scorers. Liverpool‘s Darwin Núñez, Chelsea‘s Nicolas Jackson and even Aston Villa‘s Ollie Watkins all fit this mold to some extent — players who contribute both goals and assists, whose off-ball movement facilitates their team’s attack as much as their ability to kick a ball into a goal. Just like Arsenal are poised, Liverpool, Chelsea and Aston Villa are all going to set a single-season club record for the number of pullbacks attempted.

The same goes for Brentford, the club whose playing style is the most directly shaped by data analysis. It’s also true for Newcastle United, who have had to figure out a way to create goals after defenses realized they had to drop deeper and play Eddie Howe’s side like they do the other top teams in the league. And it’s also true for Burnley, who have been relegated but who have attempted more cutbacks than 2016-17 Chelsea and 2018-19, the teams with the sixth- and fourth-most points, respectively, in the history of the Premier League.

Led by Pep Guardiola, the coach who guided the club that perfected the pullback, Manchester City have instead gone the other way. Their tendency to use the pullback peaked in 2018-19, 60 attempts, when they played Raheem Sterling and Leroy Sané as same-side wingers. Rather than cutting inside onto their strong foot and shooting, both players were naturally inclined to drive to the end line and then use their strong foot to drive the ball back toward the penalty spot.

Now, outside of Jérémy Doku, Man City really don’t have any driving wingers. But they do have a hulking center-forward who can turn almost any pass you throw at him into a goal. With Erling Haaland on your team, you almost want to limit the number of pullbacks you play because a pullback means a pass played to someone other than Haaland. Bernardo Silva is leading Man City in the number of shots attempted from pullbacks, while Phil Foden and Rodri, a theoretical holding midfielder, have attempted just as many (two) as City’s center-forward.

It’s hard to say that it hasn’t worked: Man City lead the league in goals and points per game. They’re probably going to win the league again. But their goals-per-game rate and their per-game goal differential are just the fifth-best marks during the Guardiola era. And if they slip up just one more time over the final two matches, Arsenal will be right there, just like everyone else: pulling the ball back toward the penalty area.